Meet the trailblazing women that made some of the world’s most important maps

&w=256&q=90)

Throughout history, women have so often been relegated to the sidelines: their contributions dismissed as unimportant, or, even worse, attributed to a man. It’s the same story in navigation and mapping. There are many women who helped shape mapmaking but are often ignored in favor of the men who were more freely welcomed into the space. Who were these women? And how did their innovations shape the modern world of mapping and navigation that we know today?

Who helped to create one of the most comprehensive mappa mundi, a medieval map depicting an illustrated guide of the world? Who popularized London’s A-Z map, a stalwart companion to many during any trip to the ‘Old Smoke’? Standing firm in their places in history, these women helped to move the navigation business forward.

Phyllis Pearsall

A British painter and writer, Pearsall was responsible for the creation of Geographer’s A–Z Map Company and inventing the iconic London A-Z map. Pearsall’s success in this area was due to her diligence as a businesswoman and as a formidable cartographer. Despite the widespread use of her maps, however, Pearsall was never commercially ambitious, preferring to use the success of her A-Z map to give her time and money to keep on painting and writing.

Though, if we dive a little deeper, we see that her story is a bit more complicated – while she is certainly responsible for the success of her mapping company, how the A-Z map came to be is under dispute.

The legend goes that a young Pearsall was wandering the streets of London, attempting to find a party she was heading to, and upon realizing that the 1919 Ordnance Survey map she was using was useless, had an idea of mapping London in a way that made it easier to follow. This became the London A-Z.

Pearsall was responsible for the creation of the London A-Z map.

Of course, there are other tales as well – how she had the idea when looking for houses of the people she’d been asked to paint and so on. Pearsall’s self-published memoirs hold most of what people know about the A-Z’s origins. Her half-brother claims that he and his father had more to do with the creation of the map than Pearsall admits, but regardless – Pearsall headed a formidable mapping business for the majority of her life, having a wide and lasting impact on the navigation scene.

In order to create the map, Pearsall walked all throughout London, writing notes and surveying the area. The process allegedly took a year, and when Pearsall found her map was rejected by the Geographer’s Map Company, she took it upon herself to publish it on her own. In 1936 she began selling the maps, which were immediately popular. As the story goes, she was so determined for her maps to be sold that she delivered one batch of them to a bookseller in a wheelbarrow, as she didn’t have the backing of an established publisher to help her with distribution.

Pearsall also played an important role during WW2: she was made head of a section in the Home Intelligence Division in the Ministry of Information, due to her detailed knowledge of mapping and the London area. Her company, despite taking a break during the war, continued to grow, with A-Z maps popping up for every major city in the world. She remained head of her company for many years, with the A-Z books remaining a staple for many people, tourists and locals alike.

Florence Kelley and Agnes Sinclair Holbrook

A notable abolitionist, Kelley also investigated working and social conditions. During the Hull House Maps and Papers project, Kelley collected data from inhabitants residing in the slums of Chicago. She ended up creating a series of maps, which were modelled after Charles Booth’s poverty maps of London. Comprised of two sets of maps, four sections of Chicago were covered. One map displayed the nationality of the people living in the buildings, and the other one showed the weekly household income. The result produced a striking visual representation of the link between people’s nationality and how financially successful they had been since emigrating to America.

However, it was Agnes Sinclair Holbrook, a recent science graduate working at Hull House, who did the majority of the designing and constructing of the physical maps. Her approach to the data that Kelley collected was an important example of statistical graphics, with Holbrook committed to displaying the data in the most accurate way possible.

The maps represented a groundbreaking new way of mapping the social and demographic characteristics of a certain area; his visualization helped to demonstrate the importance of a discipline such as social science. The joint effort of Holbrook and Kelley’s work was part of important research and charity, and helped to influence sociology and modern geographic information system (GIS) mapping.

The Ebstorf Nuns

The Ebstorf Map is one of the most well-known ‘mappa-mundi’, which is basically a medieval European map. Created around 1234, it’s a valuable historical artefact that reveals how the medieval population viewed their world. Although it was destroyed during the bombing of Hanover during World War II, black and white photographs of the map survive. An important piece of history, it was long thought to be created by Gervase of Tilbury, an English priest. However, the period in which the map was made saw the cloister where the map was found experiencing an economic revival of sorts, with the nuns there producing various forms of art, from assisting the decoration of Gothic churches, to making large carpets. The Ebstorf nuns also came from noble origins, and were allowed to travel, making it more likely that the creation of the map could be attributed to them. Despite there being no clear answer amongst scholars as to who really produced the map, there are additions to the map that are not found in Tilbury’s works, and the creation of the map aligns with what was occurring at the nunnery of the time.

The map was painted on 30 goatskins and depicted the world as it was thought to look at the time. Centered on Jerusalem, the map contained images of Christ and Rome, as well as descriptions of animals. There was also text which described the creation of the world, definition of certain words and an explanation as to why the world was divided into three parts, as was the belief at the time. Both pagan and biblical history was incorporated into the map. It was a clear representation of the zeitgeist of the time.

Both pagan and biblical history was incorporated into the map.

Marie Tharp

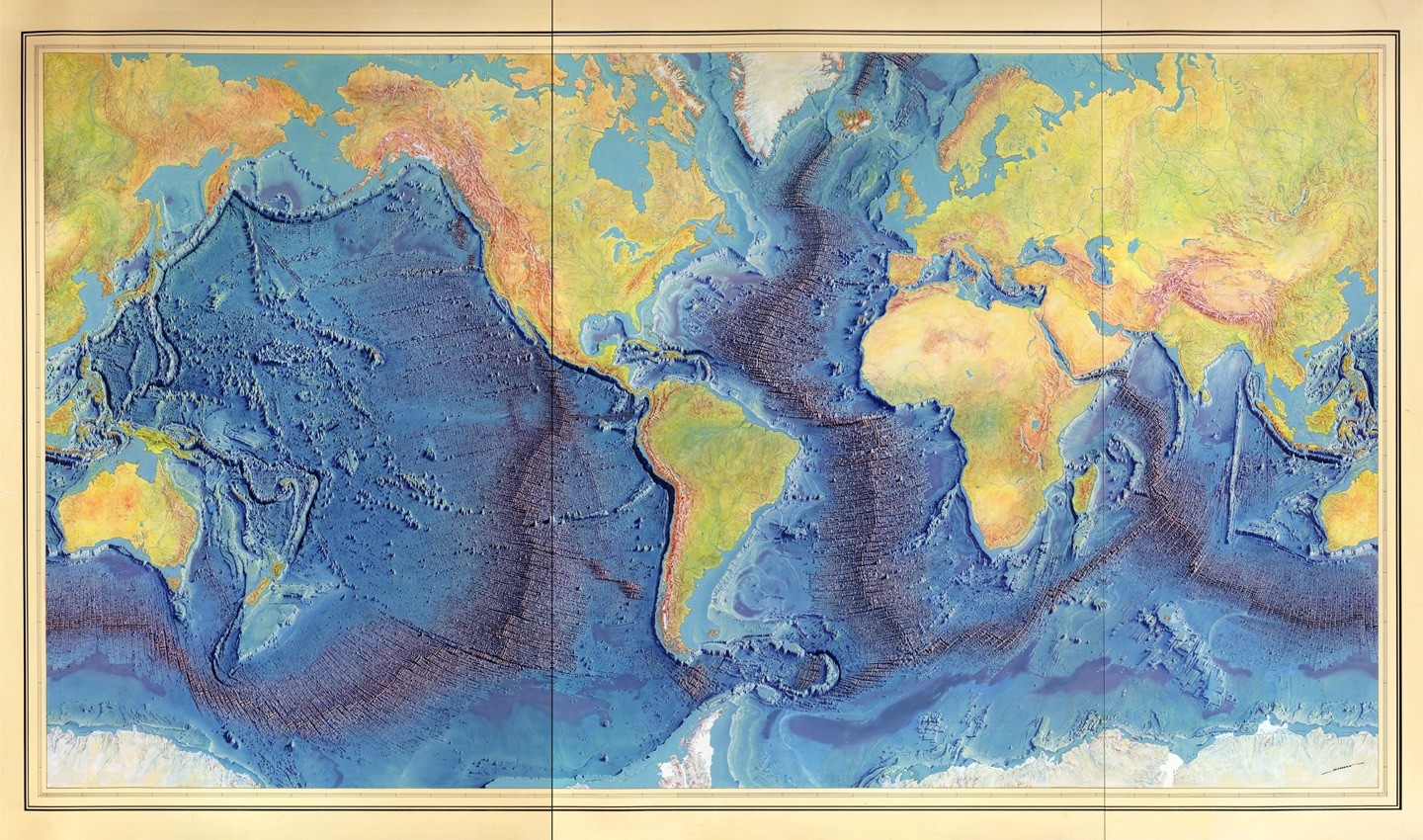

Marie Tharp was responsible for the creation of the first scientific map of the Atlantic Ocean floor. An American geologist and oceanographic cartographer, Tharp earned a masters in geology after being recruited into a program at the University of Michigan. She later met Bruce Heezen, a fellow geologist, while working in drafting at the Lamont Geological Observatory, and together the two of them began collaborating on maps. Due to women being barred from working on ships at the time, Heezen would collect bathymetric data aboard a research ship, passing it on to Tharp who would then draw maps based on what was found.

Tharp was also instrumental in proving the existence of continental drift. While drafting at the Lamont Geological Observatory, Tharp presented an anomaly she’d found to Heezen, who like much of the scientific community at the time, dismissed the possibility of continental drift. When Tharp put forth her interpretation of the profiles she’d been working on, Heezen called it “girl talk”. Nevertheless, Tharp persevered, creating a map of the ocean floor eventually with the help of Heezen and others. Her discovery of a mid-ocean rift was invaluable regarding research about plate tectonics, although with most of the scientific community opposed to continental drift, no one was able to explain how it got there. In 1956, Heezen presented the results to the American Geophysical Union in Toronto.

Tharp’s discovery of a mid-ocean rift was invaluable to research about plate tectonics.

Despite their work being a joint effort, Tharp’s name doesn’t appear on any of the papers Heezen and others published about plate tectonics. When Heezen and Tharp created their map of the entire ocean floor, it was Heezen who got all the credit. Tharp died in 2006, but has since been recognized for her groundbreaking work and has been named one of the four greatest cartographers of the 20th century in 1997, receiving double honors from the Library of Congress.

Shanawdithit

As is the problem in so many cases, cartography is dominated by the western world’s ideal of what it should look like. It should come as no surprise then, that indigenous peoples have their own history of mapping. Native North Americans played an important role in the history of mapmaking, with one of those figures being Shanawdithit.

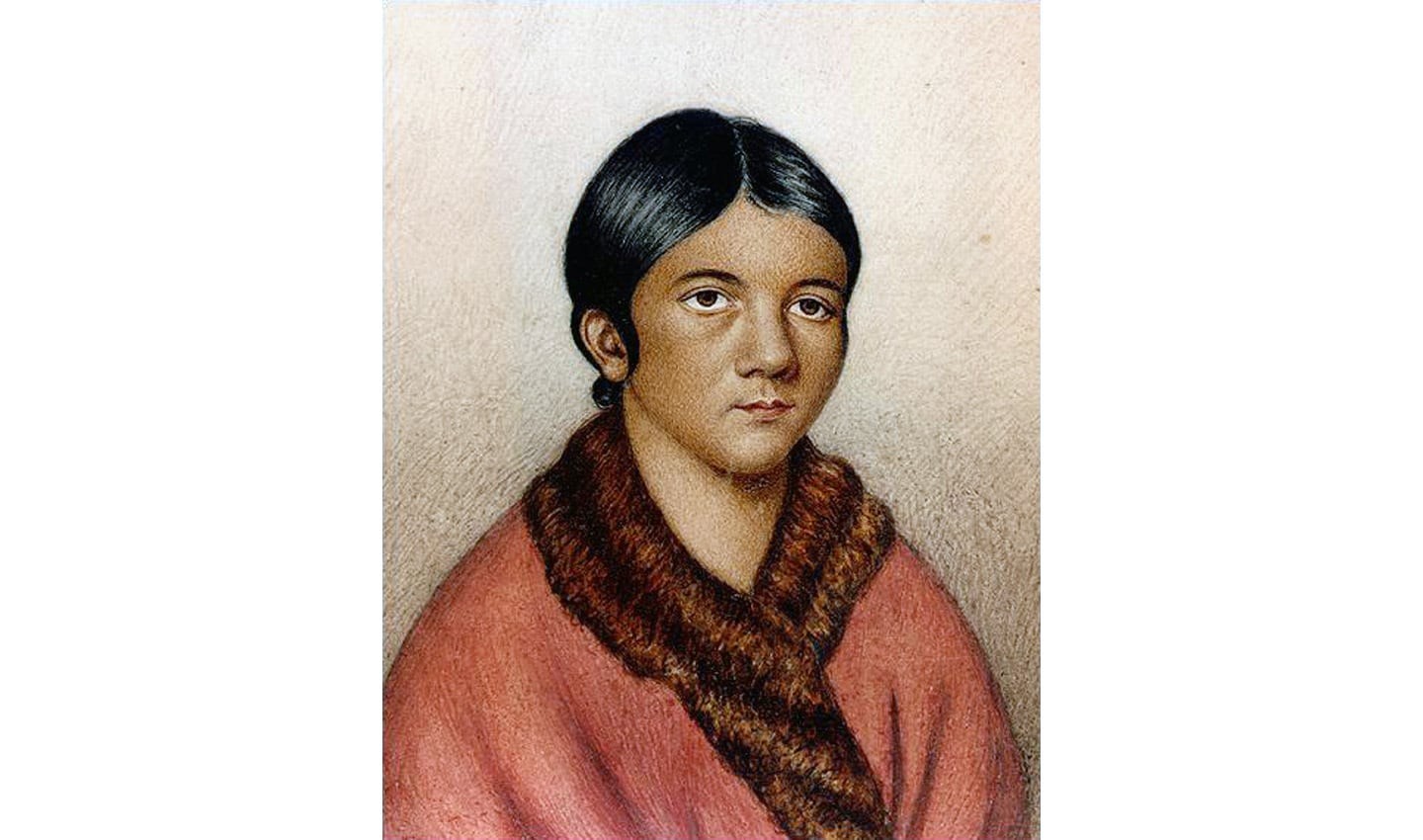

A member of the Beothuk tribe in the early 19th century, Shanawdithit lived during the particularly violent period of British colonization of Newfoundland. As a result of this conflict, Shanawdithit’s people were almost entirely wiped out, and although she died in her late twenties, she’d already come to be known as the last ‘full-blooded’ member of her tribe.

Shanawdithit was a member of the Beothuk tribe in the early 19th century.

Shanawdithit’s contribution to mapping is best seen by the five maps she created in 1829, living as a servant in a British settlement. The maps detailed her memories of her tribe’s movements and their interactions and hostilities with settlers 18 years before. According to James P. Howley, who wrote about her tribe in a 1915 book, the rivers and lakes that she detailed on her maps were created with astounding geographical accuracy. Not only were Shanawdithit’s maps a record of the landscape she grew up in, but they also documented the horrors and violence that occurred as colonizers forcefully claimed indigenous land.

A lasting record of the Beothuk language, customs and beliefs, the maps are a reminder of indigenous treatment at the hands of settlers, as well as an important display of historical mapping. Without having access to the tools that Shanawdithit’s cartographer contemporaries had, she still managed to create a map with a great deal of accuracy, demonstrating a different form of cartography.

Mary Ann Roque

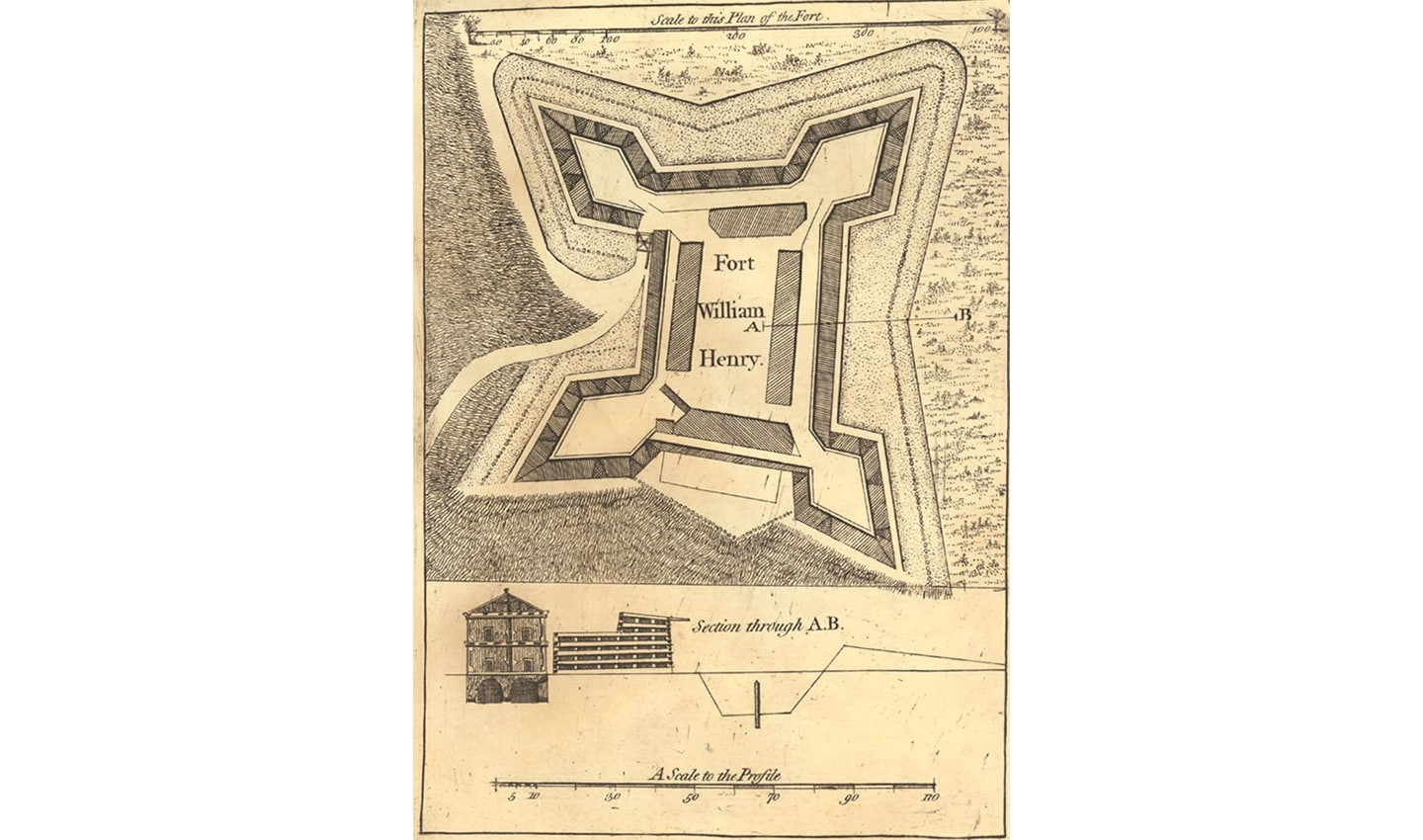

When well-known 18th century English cartographer John Roque died, his wife, Mary Ann Roque, carried on their business from The Strand in London, continuing to sell and print the maps he had made. However, Roque published new maps beside her husband’s, releasing an atlas booklet called ‘A Set of Plans and Forts of America’ in 1765, which is now considered one of the earliest published maps of Albany, New York. Roque’s publications are still available in many public libraries, such as the National Archives and the British Library.

Roque, like many women of her time, used her initials on her publications - a marketing technique that was employed in order to hide her gender from the public. This meant that Roque was hidden from history, often only referred to as just ‘the wife’ of John Roque.

Roque’s published maps are still available in public libraries today, such as the National Archives.

Regina Araujo de Almeida

Almeida, currently a Professor of Geography at the University of Sao Paulo, is the leading cartographer in tactile mapping. Tactile mapping introduces raised area for landmass, different textures for water and Braille for land names. This allows visually impaired people to be introduced to mapping and learn about geography. Almeida’s introduction of tactile mapping, paired with her position as a teacher of geography, highlights an important part of society that is overlooked when it comes to navigation.

Almeida has also spent the majority of her career bringing cartography to minority groups, such as disabled people and Indigenous populations. She would spend weeks at a time immersing herself in the culture of several Indigenous groups living in the Brazilian Amazonian region, imparting her navigational knowledge and then in turn learning about their concepts of space, drawings and maps.

Almeida’s contribution to mapping is not just based on landscape but also the social side of cartography – the need for equal opportunities and opening space up for every person. Through tactile mapping and education, Almeida helped to bring mapping to the wider world and began to erase the boundaries that have barred people from taking part for so long.

Almeida is a leading cartographer in tactile mapping.

The hidden figures in the mapping industry

It’s not surprising that like with so many other areas in history, women have been in the shadows. It’s time that they are given the recognition they deserve as pivotal figures in the navigation industry. This list of trailblazing women is only the tip of the iceberg – there are figures today who are having a large and unmistakable impact on mapping and navigation, from Judith Tyner, who introduced the concept of ‘persuasive cartography’ in order to better understand the subjectivity key to map making, to Kira B. Shingareva, who was one of the first people successful in mapping the dark side of the moon.

Women who perhaps never had their name noted in history books, or whose accomplishments were never realized reside in every part of history, including navigation. Without Marie Tharp, the Atlantic Ocean floor might still be unmapped, and scientists might have taken longer to accept the theory of continental drift. Without Shanawdithit, we might not have an astonishing remembrance of the Beothuk people and what they suffered at the hands of colonialism. And without Regina Araujo, learning about mapping might still be restricted to the privileged few, rather than having been extended to the many. Shedding light on the women cartographers that helped the industry become what it is today is a necessity, a spotlight on a key part of navigational history.

People also read

)

More than 20 years of mobile mapping, here’s how it began

)

Women in tech need other women in tech

)

Get to your next destination faster with personalized searches in AmiGO

* Required field. By submitting your contact details to TomTom, you agree that we can contact you about marketing offers, newsletters, or to invite you to webinars and events. We could further personalize the content that you receive via cookies. You can unsubscribe at any time by the link included in our emails. Review our privacy policy.